Script Adjustments

Welcome back, everybody! Over the weekend, I turned another year older. Another year wiser, as well? Let’s see, as I dig into the Comix Counsel mailbag:

Given the medium of comics, and the idea that exposure can breed new opportunities/ways of thinking about something, are there ways in which your storyboard layouts or completed visual pages of material (just sequential art, no text) inform/inspire some of your script-writing? I’m asking because I’m wondering since I have yet to see any completed pages/layouts, I’m wondering if my scripting experience pre-pages will be different from that post-pages?

In truth, I had to read the question a few times to get to the heart of what its author was asking. But given what I know about him (he’s an aspiring comic book writer currently working on his first set of scripts for what he hopes to be a large ongoing project), I get it. He’s wondering whether or not his scripting (in this case captions and word balloons) will change (or is it okay to change) in the time between when he writes the scripts and when he gets the finished art back. It’s an good question.

Back in the day, Stan Lee/Marvel method writers would always wait until the finished art came in before writing the finished dialog and captions. Their scripts were essentially story outlines or beat sheets, which their artists would translate into 22 pages of sequentials, and then pass back to the writer to put the actual words down on the page. I think it’d be an interesting challenge to work this way, but as a storyteller, I feel the Marvel method doesn’t give the writer nearly enough control over the story. That method has gone largely out of fashion, and most writers today work in full script format. This means things like page breakdowns, pacing, number of panels, angles of shots, and yes the actual words that show up on a page, are something most artist’s today are going to expect to find in scripts.

However, as a collaborative medium, no page a writer gets back from his artist is going to be EXACTLY what he or she envisioned. (If you are lucky, you’ll be work with an artist who routinely delivers pages that are BETTER than what you imagined.) Whether it’s a layout choice, a camera angle, facial expression, or extra detail drawn on the page, the page you get may differ from the one you expected.

Likewise, as the author of the question alluded to, a good writer is always trying to learn more about the craft of writing comics. Given that it can be weeks (or months, or years) between submitting a script to an artist and getting the finished pages back, it’s quite possible the writer will know more about what works and what doesn’t in a script at that point. Is it common then to make changes?

Again, it’s a good question. Here are my thoughts on the matter:

1.) It’s almost always the case that you’ll make scripting changes after receiving the original art.

2.) That’s not an excuse to half-ass your writing with an “I’ll script it when I see it” attitude.

To illustrate, let’s look at an example scripting change from my own work I had to make last week. Here’s my script for a panel in my fantasy book Tears of the Dragon:

Panel 1- We are in the King’s War Room. THORNGILL is in the foreground on the lefthand side of the panel, stroking his chin in thought. In the Midground, we see King Torvuld sitting on his throne, hands together also in thought. Attiem stands next to him, and offers counsel.THORNGILL -It shames me to admit, I had not considered a direct attack on the Hornak. But their caves-

ATTIEM- Can be navigated by the right guide.

TORVULD- If Attiem says he can lead you to the Hornak, then it is so.

Now quick, who can tell me how I messed up here?

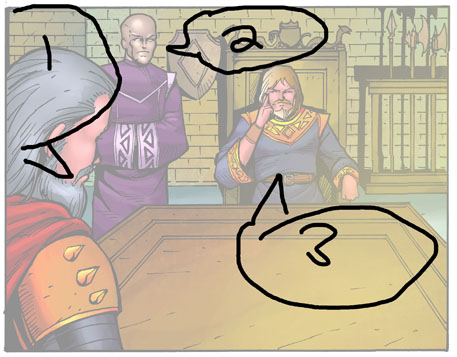

Perhaps it’s not obvious in the panel description, but it clearly was when I got the art back:

The panel Koko Amboro delivered looks great, and it’s exactly what I called for in my script. The only problem is, it’s impossible to lay my dialog down here.

My script called for the speaking order to be THORNGILL, ATTIEM, TORVULD. That’s the order the word balloons should be read in. However, here’s what that would have to look like:

To get in THORNGILL’s lines in the spot it’d naturally want to be read, I’d basically need to cut off his head. This calls out the mistake I made in my script. I called for Attiem to be “next to the King.” That’s what Koko gave me. However, I should have said “to the King’s left” or “next to the King on the far right side of the panel.” This would have left room for Thorngill’s dialog.

To get in THORNGILL’s lines in the spot it’d naturally want to be read, I’d basically need to cut off his head. This calls out the mistake I made in my script. I called for Attiem to be “next to the King.” That’s what Koko gave me. However, I should have said “to the King’s left” or “next to the King on the far right side of the panel.” This would have left room for Thorngill’s dialog.

Of course, I didn’t, and I’m not about to make Koko change his art to make up for my failings as a writer. So, what other options do I have? What if I put the balloons in a spot where there was more room?

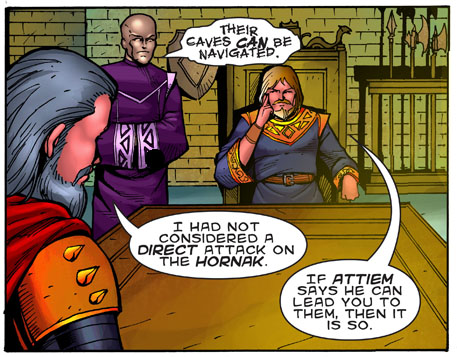

Visually, this is good position of word balloons. They’re not cutting off figures, and well positioned. However, in this case, they’ll be read 2, 3, 1. And that won’t work.

Visually, this is good position of word balloons. They’re not cutting off figures, and well positioned. However, in this case, they’ll be read 2, 3, 1. And that won’t work.

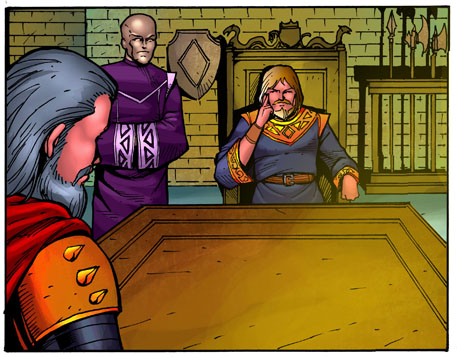

Sometimes, you can get creative. (Or desperate.) Perhaps a Panel flip will save the day?

Nah. That’s still awful. And not a habit you want to be making.

Nah. That’s still awful. And not a habit you want to be making.

As it turns out, the simplest, easiest way to solve the problem I created here, is to SCRIPT my way out of it. I ended up changing the order of speakers to be: ATTIEM, THORNGILL, TORVULD. To do so, I’d have to change the actual words on the panel a bit, and ended up eliminating a few along the way. Still, the story beat for the panel is exactly the same.

Situations like this is one of the reasons I advocate writers learn to letter. Sure, a good letterer might bring this problem to the writer’s attention, along with some potential solutions. But an overworked letterer, or one who doesn’t care about the story as much as you do (and that’s probably all of them) might just try to force it to work.

Situations like this is one of the reasons I advocate writers learn to letter. Sure, a good letterer might bring this problem to the writer’s attention, along with some potential solutions. But an overworked letterer, or one who doesn’t care about the story as much as you do (and that’s probably all of them) might just try to force it to work.

However, it’s worth noting that ALL of this could have been avoided, had I done a better job in the scripting stage. You don’t want to be figuring out things like characters voices, or what will and won’t fit on a page at the lettering stage. Comic scripting is like carpentry. You want to measure twice (or three times) and cut once. This is why you need to do multiple drafts of your work, and develop a trained eye that sees the entire finished page well before it is complete. And this is where an editor can save you a ton of frustration.

So, that’s where I stand on the issue. What about you guys? Are you finding yourself making a ton of adjustments to scripts as you get art back? If so, is this a bad thing? As always, love to hear your thoughts below.

And, if you have a question you’d like to hear me tackle in a future installment of Comix Counsel, shoot me an email at tylerjamescomics@gmail.com.

***

![]() Tyler James is a comics creator, game designer, and educator residing in Newburyport, MA. He is the writer and co-creator of EPIC, a superteen action comedy, and Tears of the Dragon, a swords and sorcery fantasy. His past work includes OVER, a romantic comedy graphic novel, and Super Seed, the story of the world’s first super powered fertility clinic. His work has been published by DC and Arcana comics.

Tyler James is a comics creator, game designer, and educator residing in Newburyport, MA. He is the writer and co-creator of EPIC, a superteen action comedy, and Tears of the Dragon, a swords and sorcery fantasy. His past work includes OVER, a romantic comedy graphic novel, and Super Seed, the story of the world’s first super powered fertility clinic. His work has been published by DC and Arcana comics.

Tyler is the publisher and co-creator of ComixTribe, a new website empowering creators to help each other make better comics.

Contact Tyler via email (tylerjamescomics@gmail.com), visit his website TylerJamesComics.com, follow him on Twitter, or check him out on Facebook.

Related Posts:

Category: Comix Counsel

Great piece! I’m pretty excited that I was able to figure out the problem with your script example, lol…

One of the advantages of being both the artist and the writer of a comic is that my scripts are total Silly Putty. I make script changes based on art all the time. Now, you’d think I’d never have make script changes on art because I AM the artist in my comics and that I’d be able to lay things out exactly as I imagined when I scripted them. But the thing is when I’m writing, I’m just interested in getting story beats and dialogue out. Layout isn’t my number one priority at that point. It’s when I start laying out pages that I realize certain dialogue points don’t work (like your example above). It’s just part of the process. Scripts are mutable. Just go with it.

Is that really a script problem? Couldn’t it be solved by leaving more space above the speaker’s heads? (Camera tripod needs to be taller, so to speak)

Sure. It could have been solved in the art stage. However, it wasn’t. Maybe the artist should have caught that, but again, I could have made it clearer for him. Either way, once the art is complete, options are limited…so here, scripting my way out was the best option available.

Yeah, I don’t think that was caused by a script problem. Additional hand-holding in the script may have prevented the error, but an artist really should be taking the order of the dialogue into account when he composes a panel.

Still a good save, on the writer’s part, though.

Actually, it’s not that much of a scripting problem, but an editorial/procedural problem.

If this had gone through an editor, the editor probably would have caught it. But, let’s say s/he didn’t.

The next step should have been thumbnails. THAT would have caught the problem right there.

Was it thumbnailed? I don’t know. But thumbnails should be an important, NEEDED step in EVERY project’s creation. It will sort out a LOT of potential problems.

Happy belated birthday, Tyler.

Putting a comic together is like a collaborative effort of a really great painting. There are not too many mistakes while you are working on it–only happy accidents. Allowing everyone to be as creative as they can to push the project to be better is definitely key! As long as everyone realizes what the goal is, you typically see a better product by letting creativity takes its course at each stage. No one but the writer will see any “mistakes”. The reader just sees the final.

Steven Forbes has great advice. Reading the script with thumbnails in panel/page breakdowns at least gives the editor an idea of what kind of problems to expect in the final and can sometimes catch things if they are urgent enough. Sometimes going forward is still a better time-saving option than tweaking too much before hand. Creators have a way of pulling off some surprising good solutions sometimes.

I actually started to thumbnail instead of writing scripts for exactly this reason. (Helps that I’m the writer, artist and letterer). Also saves the “oh dear too much dialogue too little space for the pretty art” issue.

I’m thinking along the line of what Daniel and Khat just mentioned. Although if physically pains me to draw anything (chronic pain/complex regional pain syndrome) little thumbnails along with the storyboard seems the way I’ll go long term as well.

James, here’s a workflow that should work for you when you’re working with an artist:

You write the script (and get it edited).

Give the (edited) script to the artist.

The artist goes through the (edited) script and starts plotting out the panels and pacing.

The artist does thumbnails, and gives them to you (and your editor) for approval.

Any changes that need to be made should be made at this stage. This is a step that a LOT of new creators just leap over. They go straight from script to finished pages. Unless you’re working with a veteran artist, this isn’t a step that should be skipped. (And even if you ARE working with a vet, this isn’t a step that should be skipped.)

Once the thumbs are approved, the artist then starts on finished pencils.

Everything else goes forward from there.

Hope that helps. (And saves you from having to pain yourself.)

Thanks Steven. 🙂

I always insist on pages sketches, before pencils to see how the page looks like. I find it odd that someone would hand over a script and let an artist go straight to the finished pages.

I’ve been following David Nakayama’s storyboard animation sheets on deviantART and was thinking that it would be neat to be able to write and sketch out the panel shots for reference. But holding a pen, pencil or stylus for longer than a minute or two plays havoc on my hands.

No worries, James.

Unless you have some artistic ability, all you have to worry about is typing when it comes to your hands. Just make sure you’re being clear.

You guys are right. Layouts probably would have saved me in this case. And for most of my projects, I tend to have a layout review with the artist.

For TOTD though, we tend to only work that way for covers and such. In general, it’s not something I recommend, but to hit the release schedule we’ve been on, it’s sort of become practice.